Pedagogic Resources on Chinese Painting Villages

26 June 2009 / external, pedagogy, referenceBelow are some resources about the “Chinese Painting Village” phenomenon, such as Dafen or Wushipu in Shenzhen, which employ about 10,000 artists and produce more than 60% of the world’s oil paintings. The information below may be ‘of interest’ to arts educators and/or students, particularly those studying painting. I am grateful to Clement Valla for awakening me to this important trend.

For those not familiar with this phenomenon, here are the basic facts:

- About 8,000-10,000 “painting workers” are employed in a single village (actually, an urban district) to produce more than 60% of the world’s paintings. (And I’ll bet you thought the world’s largest population of artists was in Berlin or Brooklyn!)

- Some factories specialize in reproducing famous Western masterpieces; others specialize in creating literally thousands of identical units (for hotels, cruise ships, and retail outlets like WalMart, K-Mart, Ikea, etc.); and other factories specialize in painting custom reproductions of family portraits, pets, wedding photos, and the like.

- Commissioning a custom painting is done with digital images, via email attachments and PayPal, and takes about 10-14 days including shipping. Prices range from as little as $10 to as much as $1000 (for a high-quality forgery); cost factors include the size, thickness of paint, and presence of (for example) people and/or portrait faces. For a painting whose dimensions are 50cm x 40cm, one might expect to pay $30-100 US.

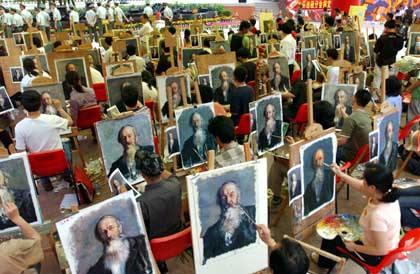

A painting speed competition in Dafen.

Newspaper articles, critical histories and other journalism.

(Lots of good information here.)

- James Fallows, “Workshop of the world, fine arts division.” Atlantic Monthly, 12/19/2007.

- James Fallows, “A little more about the ‘art factory village’ of Dafen“. Atlantic Monthly, 12/20/2007.

- Le-Min Lim, “China’s Factory for Fake Art Tries to Beat Slump“. Bloomberg News, 9/24/2008.

- Evan Osnos, “Chinese village paints by incredible numbers“. Chicago Tribune, 2/13/2007.

- Martin Paetsch, “Van Gogh From the Sweatshop“. Spiegel Online, 08/23/2006.

- Wong, Winnie Won Yin. “Framed Authors: Photography and Conceptual Art from Dafen Village“. Yishu- Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art.

This 7-minute YouTube video provides an excellent overview of the painting economy in Dafen village:

Example painting factories online.

(There are many others.)

Western art approaches to the phenomenon.

(Interesting work which addresses this trend critically, conceptually, and/or politically.)

- Michael Mandiberg. In memory of the man in front of the tanks (Tiananmen 20 years later). 2005-2009 [More at Flickr]. Mandiberg commissioned paintings of the famous Tienanmen photograph, obtaining results which were censored or modified in a variety of ways.

- REGIONAL OFFICE design group. Self-portraiture and emerging artistic consciousness in Dafen. 2007. REGIONAL OFFICE commissioned self-portraits of the Dafen artists themselves.

- Alan Butler. The Image Factory, 2009.

Butler commissioned a painting of the first photograph above (of a painting competition in Dafen village, from Spiegel Online). - Michael Wolf. Real Fake Art series.

- Christian Jankowski, Super Classical exhibition at Maccarone Gallery, 2007.

- Clement Valla:

- Paintings from Wushipu, 2009.

- 100USD-90USD-65USD, 2008.

- “Original Copies” (RISD MFA Thesis, PDF format), 2009, pp. 24-59.

Valla commissioned a variety of experiments, including the creation of painted feedback loops, open-ended instructional paintings, and paintings corrupted by digital transmission errors. His thesis provides an excellent discussion of the aesthetic and ethical issues.

Outsourced oil painting is the new “digital output”.

I should perhaps briefly explain my interest in this phenomenon. Of course, there is some very provocative conceptual art which investigates and appropriates these painting resources, such as that by the artists linked above. This is challenging and (in my opinion) necessary work. From my standpoint as an arts educator, however, I do not believe it is adequate for students to be made aware of such clever projects in blogs like this one. Instead, I believe it is essential to directly expose students — particularly those who consider themselves to be painters — to the actual use of this inexpensive, new, internet-enabled “means of production”, and thereon to crucial aesthetic and ethical questions about authenticity, labor, and the cultural logic of mass customization in today’s global economy. They must cause one to be made, once, themselves. They must understand the implications, by being implicated in the process.

Most of my undergraduate students self-identify as painters. Many of them harbor charming ideas about the “aura” of original paintings, which allows them to distinguish their works from “banal”, machine-produced prints. But too few are aware of this extraordinary revolution in their own trade, in which the majority of the world’s paintings are now mass-produced by a superscaled “human machine”. And very few, if any, yet appreciate that the cost of having a JPEG image skillfully painted in China is roughly the same price as having it printed on the HP Designjet in our school’s Digital Print Lab — or that the process of commissioning such a painting over email, is barely more complicated than pressing Command-P. (Perl script, anyone?) I am convinced that our young painters must confront these facts directly. This coming September, in my introductory Electronic Media Studio class at Carnegie Mellon, I’ll be exposing my freshmen Art students to this, in their first week at university — when their Photoshop assignments (a “fiction or forgery” collage, or a “retouched self-portrait”, perhaps) are “printed out” (surprise!) in hand-applied Chinese oils. I’m hoping this will be an eye-opening introduction to art school, and one that makes them think hard about what it means to be a painter in 2009. Stay tuned!

Thanks to Clement Valla and Winnie Won Yin Wong for invaluable pointers for this post.

« Prev post: A Juxtaposition: John Cage vs. Sam Taylor-Wood

» Next post: New Media Artworks: Prequels to Everyday Life