Printed from www.flong.com/texts/essays/essay_sonicacts_2006/

Contents © 2020 Golan Levin and Collaborators

Golan Levin and Collaborators

Essays and Statements

- Peer-Reviewed Publications

- Essays and Statements

- Interviews and Dialogues

- Catalogues and Lists

- Project Reports

- Press Clippings

- Lectures

- Code

- Misc.

- 03 2015. Brown & Son (Catalogue Essay)

- 03 2015. For Us, By Us

- 05 2009. Audiovisual Software Art: A Partial History

- 07 2006. Hands Up! The 'Media Art Posture'

- 07 2006. Some thoughts on Maeda for Ars 2006

- 07 2006. Einige Gedanken zu John Maeda

- 02 2006. Notes on Visualization Without Computers

- 10 2005. Artist Statement, October 2005

- 09 2005. Three Questions for Generative Artists

- 07 2005. Net Vision Jury Statement, Prix Ars

- 07 2005. Net Vision Jury-Begründung, Prix Ars

- 12 2004. Computer Vision for Artists and Designers

- 08 2003. Essay for John Maeda's Creative Code

- 01 2003. Pedagogical Statement

- 11 2001. Essay for 4x4: Beyond Photoshop

- 10 2001. Statement for Graphic Design in the 21st C.

- 10 2001. Statement of the Jury, Berlin Transmediale

- 05 2000. Statement For Communication Arts

- 12 1999. MIT Thesis Proposal

- 12 1997. MIT Statement of Objectives

Some Notes on Visualization Without Computers

Presented in a Lecture at Sonic Acts XI, Amsterdam, Holland.

Golan Levin, 25 February 2006. Revised 29 June 2006.

In my role as a professor in a Fine Arts academy, I am an emissary for computer arts. Among my duties, I teach very introductory courses to first-year students in order to ensure that they have at least a rudimentary literacy in common electronic tools like Photoshop. Although I try to expose my students to a wide range of new-media art possibilities, the majority of my students expect to become painters, so learning how to use the Adobe desktop suite is usually about as much immersion in the computer world as they can stand. Perhaps only one in thirty of my students will develop a curiosity about the artistic potential of computation, which is to say programming, as a medium.

Since I have so few students who can program computers, and many students with relatively little interest in doing so, I've recently tried to encourage the development of procedural thinking skills independent of programming. One might call it "programming without computers." I think this mode of thinking is increasingly relevant anyway to contemporary life, and contemporary art, even if one doesn't end up writing code.

A few days ago I was talking to some students, and while digressing I casually complained about an algorithmic problem I was having. And a smart but computer-illiterate first-year student of mine, for whom the computer has presented nothing but frustrations and obstacles, asked me one of those questions that, on consideration, really shook my assumptions: Why do you make your art on computers?

Of course I have a variety of ready explanations about the unique affordances of computers for artmaking: the advantages of iteration for endless generativity; conditional testing for interactivity; data storage for record-keeping and pattern matching, etcetera. I offered these but in each case she countered that it would be simpler and more interesting to achieve these generative or interactive effects with plants, animals, or real people: "Generativity? Why not just grow a garden?" "I could do the same thing with a roomful of kittens, and it would be way more fun." "How is that better than having a friend hidden in a closet?"

I had to confess that the reason I use computers is that I'm just not clever (or charismatic) enough to come up with "real" solutions to the problems I'm interested in. And so instead, I've developed an addictive dependence on using, like, the most powerful machine ever invented in the history of humankind to achieve the simplest stupid things. I mean, "well sure you can visualize data or whatever, if you allow yourself to use that thing." But are computers the only option? Or the best one?

I don't think I'm alone in relying on the computer for too many things. Since many of us here today [at the SonicActs conference] are interested in topics like audiovisuality and information visualization, I'd like to offer a few examples I've found of clever people who have devised extremely economical solutions to interesting artistic problems in these areas — without using a computer. In the remainder of this lecture, I'd like to present and discuss three such projects: William Wegman's Stomach Song; Eva Teppe's visualization for Elliott Carter's Dialogue, and Stacy Greene's Lipsticks.

1. William Wegman's Stomach Song (1974).

This is the most economical audiovisual performance I have ever seen—a perfectly formed, wholly original unity of sound and image. It's also whimsically juvenile, to boot. Perhaps someday I'll post a small copy here and hope the Fair Use Police don't kill me. In the meantime, it's recently been re-released on DVD and is available from Amazon.

2. Eva Teppe's visualization for Elliott Carter's Dialogue (2005).

Suppose you're a new-media artist, and you are asked to "visualize the music of a live orchestra." You get to thinking: well, I'll need a 24-track audio card and a bunch of microphones for good signal separation, and some FFT code for audio analysis, and a fast graphics card.... Or you could just rely on the same hardware as Wegman: the face and the brain. This stunning visualization, created by German video artist Eva Teppe, accompanied a performance by the Bruckner Orchester Linz at the 2005 Ars Electronica Festival, with Dennis Russell Davies conducting. Unfortunately, there's not much documentation available: just a few photos here.

In this visualization, Teppe videotaped the faces of people listening to a recorded version of the concert. These face-videos were then presented while the orchestra performed the same music. The conductor gamely kept the orchestra to within ± 3 seconds of the timing of the original recorded version. The result? Each subject's face portrays a different visualization of the music—a completely subjective, enormously multidimensional representation which is organically derived from the psychological impact of Carter's music on the unique personality and tastes of each subject, and our own subjective proclivities as interpreters of facial expressions. Viewing the performance, we each begin to identify with one or more of the subjects, based on the similarity of their reactions to our own. We develop a mental model, not only of the music we are listening to, but of the personalities of each of the subjects. We may even laugh when a subject's expression confirms our own inner feelings. This is the richest visualization I have seen.

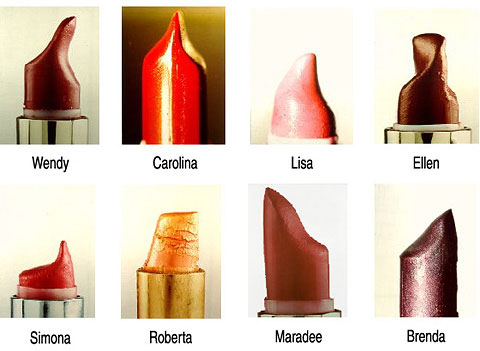

3. Stacy Greene's Lipsticks (1991)

In this photo series, Stacy Greene presents oddly comprehensive portraits of twenty women by simply photographing their lipsticks. Each unit hints, but just hints, at a highly multi-dimensional redaction of many personal features, encoding such factors as personal style, complexion, tidiness, a specific gestural motion.... We observe each lipstick and suspect we know something vague about its owner—or perhaps we know something quite specific about who they are not. Greene's visualization appears in Speck: A Curious Collection of Uncommon Things, by Peter Buchanan-Smith, and on Greene's web site.